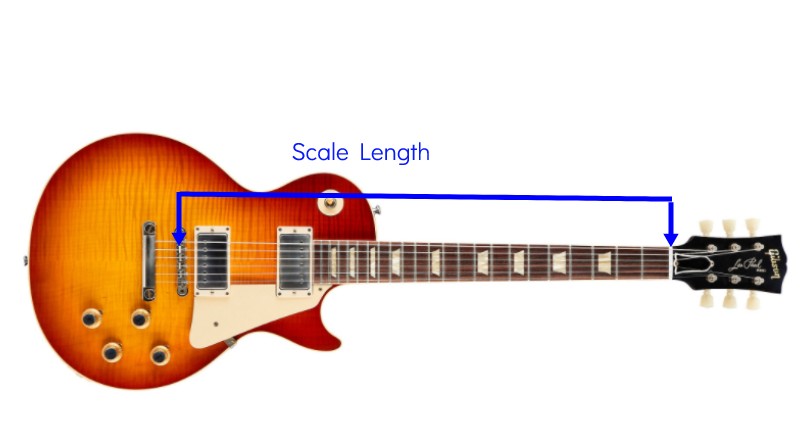

The scale length of a guitar is the distance measured from the nut to the bridge. There is no particular standard for scale length set among guitar manufacturers, as different scale lengths will provide different playing characteristics.

In today’s article, we are going deep on everything related to scale lengths – how to best measure it, what are common scale lengths, and how a scale length can impact the playability of your guitar.

Some key points about scale lengths are:

- Scale lengths can influence string action, fret buzz, and string tension

- Shorter scale lengths can make strings easier to bend

- Longer scale lengths can make your strings feel tighter and more stable

- Bass guitars have scale lengths that are much longer than traditional guitars

Contents

Scale length basics

The scale length of any fretted instrument (guitar, bass, even ukulele, etc.) is simply the overall distance from the nut to the bridge.

To measure the scale length on your guitar, you may think all you have to do is take a tape measure and go from, again, the nut to the bridge. Simple enough, right? Well…not exactly. We said ‘overall distance’ for a reason…

That’s because no two strings have precisely the same scale length. Why? Because setting intonation plays a significant factor. For a guitar to have proper intonation, you’ll find that each string saddle on the bridge is typically adjusted to a different point from the nut. So you’ll have some variance…and none of the strings is the ‘right’ one to take as the prime measurement.

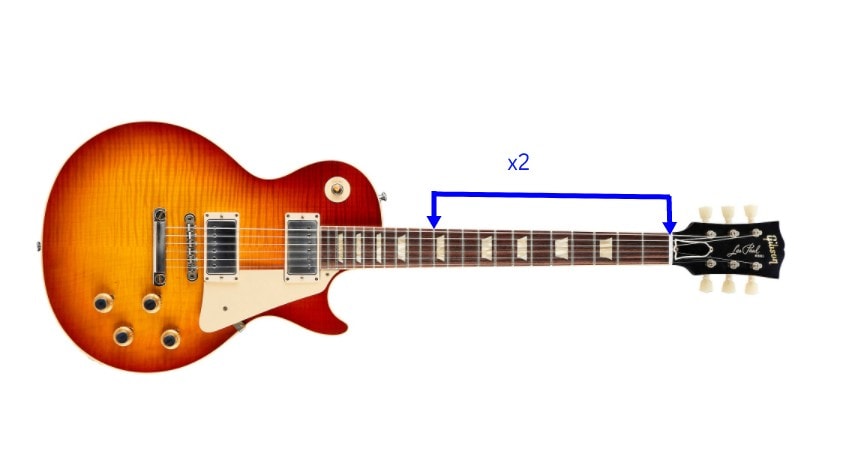

A much easier way to tell is to measure the dimension from the nut to the top of the 12th fret. Once you have that, multiply it by 2. That will give you the ‘overall distance,’ which is ultimately referred to as the ‘scale length.’

Do guitars have different scale lengths?

Yes – they certainly do! Not only are scale lengths different depending mostly on the manufacturer’s design, but there are also often several models within a brand’s product line that vary as well.

Most Gibson models have a scale length of 24-¾”, but that exact figure has varied somewhat over the years. It’s not uncommon to find recent Gibson guitars that have a 24-⅚” scale length.

Fender’s most iconic models (the Stratocaster and the Telecaster) clock in at 25-½” with models such as the Jaguar having a shorter 24” scale length. PRS guitars typically have a 25” scale length across all their models.

Taking a look at acoustic guitars, most Martin acoustics have a scale length ranging from 24.9” to 25.4”. Taylor guitars come in at 24-⅞” except their Mini series, which comes in at 23-½”.

Scale Lengths Of Popular Guitars

Fender

- Fender Duo-Sonic – originally 22.5 inches, 24 inches on reissue, plus a rare 22.7 inch model exists

- Fender Esquire – 25.5 inches

- Fender Jaguar – 24 inches

- Fender Jaguar Baritone Custom – 28.5 inches

- Fender Jaguar Baritone Special HH – 27 Inches

- Fender Jazzmaster – 25.5 inches

- Fender Musicmaster – 24 inches and 22.5 inches

- Fender Mustang – typically 24 Inches, rare 22.5 inch model exists

- Fender Stratocaster – 25.5 inches

- Fender Swinger – 22.5 inches

- Fender Telecaster – 25.5 inches

Gibson

- Gibson ES-335 – 24.75 inches

- Gibson ES-345 – 24.75 inches

- Gibson Explorer – 24.75 inches

- Gibson Firebird – 24.75 inches

- Gibson Flying V – 24.75 inches

- Gibson Hummingbird – 25.5 Inches

- Gibson J-185 – 24.75 inches

- Gibson J-45 – 24.75 inches

- Gibson J-50 – 25.5 Inches

- Gibson L-00 – 24.75 inches

- Gibson Les Paul – 24.75 inches

- Gibson LG-2 – 24.75 inches

- Gibson SG – 24.75 inches

- Gibson SJ-200 – 25.5 Inches

- Gibson Southern Jumbo – 24.75 inches

PRS

- PRS 245 – 24.5 inches

- PRS 509 – 25.25 inches

- PRS Custom 22 – 25 inches

- PRS Custom 24 – 25 inches

- PRS Fiore – 25.5 inches

- PRS Paul’s Guitar – 25 inches

- PRS McCarty 594 – 24.594 inches

- PRS Silver Sky -25.5 inches

How does scale length affect playability?

The scale length of your guitar has a significant influence on how well it plays. There are several playability factors that scale length can affect. Understanding how those factors work can help when trying to select the best guitar for your preferences.

Fret spacing

One of the first things you’ll notice when playing a guitar with a different scale length than you’re used to is the distance between the frets. On guitars with larger scale lengths, the frets are spaced farther apart; on the flip side of that, smaller scale lengths mean your frets will be closer together.

So it makes sense to say that shorter scale guitars may be a little more challenging to finger chords on if your hands are a bit on the bigger side. In fact, it’s very common for short scale guitars to be the first choice for children (and some adults) as they can be more comfortable to play when you have smaller body proportions.

Fretting chords is one thing, but the same phenomenon is true for the fretboard’s upper ranges. With a smaller fret spacing, short scale guitars may be a bit more difficult to solo on past the 12th fret simply because there’s less room available for your fingers.

String tension

If you take two guitars with different scale lengths, string them up with the same gage of strings, and then tune each to standard pitch, you’ll feel a distinct variance between the two as far as the string tension is concerned (you can check out our full guide to guitar strings here).

This is because the shorter the scale length, the less tension is needed to get a string to ring out a specific pitch. Where this will be the most evident is when bending notes during a solo. You’ll find that the shorter scale guitars will need a lot less effort to get the notes you are bending up to.

There is a downside to this; it’s somewhat negligible, but it is there: lower string tension means that it may be easier to push strings out of tune when fretting chords. Guitars with longer scale lengths can tend to feel ‘tighter’ when forming chords, which may be of benefit to you if you’re primarily a rhythm player.

String action

Believe it or not, scale length can have an impact on how low you can set your action. String action merely is how high off the fretboard your strings are; higher action can be better for a lot of chordal playing, while low action is a preference for many players that like to play fast solos.

One of the most dreaded things for guitarists that prefer low action is the presence of string buzz. Whenever a string is struck, it has to have room to vibrate properly for the note to ring out clearly. If your action is too low, then the strings can lightly touch the tops of the frets, leading to that buzzing sound that drives some players nuts.

One way to counteract string buzz is to play a guitar that has a longer scale length. Since more string tension is required, less room is needed for the string to vibrate. This factor alone can allow you to drop your action a bit and mitigate the string buzz effect.

Click here to read more on action!

Down tuning considerations

By now, it should be easy to see how scale length and string tension can combine to be major factors in how well your guitar plays. You can also take these properties and apply them to the type of music you prefer to play.

A great example is if you are a metal player that typically uses a lot of dropped tunings. These days it’s not uncommon for some in this genre to tune down to standard D (which the same as standard E except all strings are tuned down a full step), or even more extreme with standard C. The limit is pushed even farther by some bands that go down to standard C then drop the low C to a B.

So what does that have to do with scale length? Quite a lot, actually! If you are playing a shorter scale guitar, the string tension you may end up with when tuning that low can basically turn your guitar strings into a bunch of rubber bands.

The answer is to play guitars with longer scale lengths since more tension is required. But even that can pose a problem for some, as longer scale length guitars just aren’t for everyone, and you may think it just doesn’t ‘feel right.’

What you can do in that case is to go back to the shorter scale length but use heavier string gages. The extra tension required to get the thicker strings up to the right pitch might just be what is needed for your tastes.

What about multiscale guitars?

While they aren’t particularly common, several manufacturers build guitars that are actually ‘multiscale’ (also called ‘fanned fret’). You’ll most often see multiscale guitars that have more than six strings (7 and 8 strings, to be exact). Why is that the case? It all goes back to our discussions on scale length and string tension.

They may look a bit oddball, but they definitely can serve a purpose. Again using metal as our genre example, it’s here where you typically find the most down tunings or the overall stylistic need to play notes that are often much lower than the traditional low E found on a six string.

Think about when you are changing strings on your guitar for a minute. When you are putting that low E on, do you recall how fast it is to get it tuned to pitch (as compared to the high E)? Not only that, but the string tension to get to that low E is relatively low. Now take that same low E and try to tune down to C. You’ll definitely have some issues with that string flopping around on you, and fret buzz will be a rampant problem to deal with.

Multiscale guitars solve this problem by actually having different scale lengths set for each string. That means that the bridge will compensate for a longer scale length for the lowest bass string as compared to the highest treble string. The end result is a guitar that looks like this:

See how the frets are ‘fanned’ instead of being parallel to each other (as found on a traditional guitar)? In conjunction with the compensated bridge, that will allow for more string tension to be applied to those lower, thicker strings that will benefit from it the most.

To be sure, multiscale guitars aren’t for everyone. But given the right application, they can be the perfect tool for the job at hand.

What about bass guitars?

A bass guitar is really no different from a traditional six string because lower notes mean less string tension, which can lead to substantial playability issues. Only with a bass, take that time 10! The strings are much thicker in order to get as low as they need to go, so having a bass guitar with the ‘typical’ scale length of around 24-½” to 25-½” just isn’t going to work.

That is why bass guitars are so much longer. The additional scale length allows for greater string tension, which translates to strings that are tight enough to be playable without excessive fret buzz or experiencing tuning issues just from the movement of the string under your fingers with such low tension.

Most bass guitars have scale lengths around 34”. Variants of this can go down as low as 30” (for a ‘short scale bass’) all the way up to 36” in some cases.

The same principles also hold true for baritone guitars. A baritone guitar fits in the space between a traditional six string and a bass. It is typically tuned down to standard B (B-E-A-D-F#-B; sometimes called ‘baritone tuning’) or sometimes even standard A. The scale length for a baritone is usually around the 27” mark, with longer scale versions approaching the same 30” of a short scale bass.

Conclusion

One spec that is commonly mentioned with guitars is the scale length (the overall distance from the nut to the bridge). It’s a simple subject that’s often misunderstood, and picking the one that’s right for you can have a massive effect on how your guitar plays and feels.

Not only can scale length affect playability, but it’s also a significant factor in how low you can tune (which can be a big consideration depending on the style of music that you prefer to play).

Overall, having a solid background with understanding all that the scale length of a guitar can influence can be a big help when you are searching for a guitar that best fits your playing style and preferences. We’d recommend experimenting with a few models from different manufacturers to see which one is the ‘right’ one for you.